- Deutsch|

- English

Prosthetics / Implants

Dentures, crowns, bridges, partial crowns, zirconia, pressable ceramic, telescopic crowns, attachments, preparation, impressions, CAD-CAM, cut-back, abutment and implantation systems in Frankfurt

A denture, or dental prosthetic, refers to any type of replacement for any part of a natural tooth. Prosthetics deals with the planning, manufacture, preparation and fitting of such a replacement.

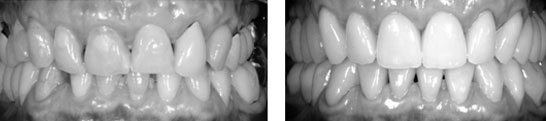

Right: An extensive prosthetic restoration following a functional analysis and Wax-up. This involved deploying full ceramic veneers, abutments, partial crowns and zirconia crowns

Right: An extensive prosthetic restoration following a functional analysis and Wax-up. This involved deploying full ceramic veneers, abutments, partial crowns and zirconia crowns

Prosthetics is the branch of dentistry that deals with the replacement or restoration of missing or damaged teeth. It requires a mastery of a set of related disciplines including the biological, functional psycho-social, material and technical aspects of prosthetics.

Prosthetics requires interdisciplinary co-operation with related medical and dental disciplines. Apart from regaining the original oral structure and improving the patient’s quality of life, it is also important to consider general organic improvements, which may require physiotherapy and psychological counselling.

It is absolutely essential when dealing with prosthetics that it is preceded by a thorough-going investigation of the whole stomatognathic system (comprising the mouth, jaws, and closely associated structures). An important – and indeed essential – diagnostic aid is radiography, which can provide information about the structure of teeth and how they bed into the jaw (the periodontium).

Additional diagnostic aids are the taking of impressions of both jaws, and the subsequent analysis of plaster models, which enables the analysis of functional features (see Reconstruction and Function). The analysis of the specific case is then completed by carrying out a functional analysis that models the movement available to both jaws and their embedded teeth. If required, splint-therapy helps stabilise the facets of teeth that are used to break down food into smaller elements.

Finally the teeth are represented in a wax-up, which enables the dentist to match the information obtained in the various analyses with the goal of the therapy (e.g., elevating the bite, replacement of dentures, the rectification of mistakes, or the realigning of bite surfaces); for further information see Function.

Preparation

Preparation should in principle be minimally invasive and seek to remove as little as possible of the remaining teeth, taking fully into account the relevant functional aspect of the teeth to be treated. (Also see Publications – CASE REPORT I&II)

Those to be capped by a crown will receive a circular preparation, whereas one that is to receive a partial crown, a veneer, or an inlay will only be partially prepared. This is done with the greatest precision, using dental surgeon’s magnifying glasses, which guarantees that the minimal amount of tooth substance is removed. An elegant restoration is further enabled by the dental technician using the most modern materials for the reconstruction, as well as for subsequent bonding or cementation.

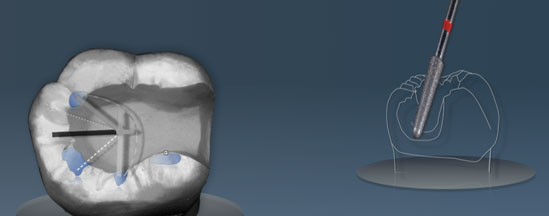

Showing the preparation for an inlay, with a projection of the occlusal compass on the tooth (left), with a dental milling instrument (right). The area in blue shows the surface of the tooth that comes into contact with the antagonistic tooth by the movement of the lower jaw to grind food.

Showing the preparation for an inlay, with a projection of the occlusal compass on the tooth (left), with a dental milling instrument (right). The area in blue shows the surface of the tooth that comes into contact with the antagonistic tooth by the movement of the lower jaw to grind food.

A smooth preparation is required for ceramic restoration to minimise the pressure on the prosthetic caused by biting. The occlusal compass (see Function) can represent the direction and scope of movement of the lower jaw, which is particularly useful for determining the best place to locate the joint between the natural tooth and the ceramic, particularly if that is where a tooth is functionally stressed. As a result of too much pressure, fractures or shearing can take place in that area, which sometimes makes it necessary to reduce contact, in order to reduce possible damage.

Picture of an extensive restoration of the upper teeth after 6 years. The preparation was carried out so as to retain as much as possible of the original teeth. Ceramic veneers were applied to the front teeth and partial crowns made out of pressable ceramic were used for the side teeth. This has resulted in a highly attractive and long-lasting solution. Different preparation forms were used, as represented in the pictures

Picture of an extensive restoration of the upper teeth after 6 years. The preparation was carried out so as to retain as much as possible of the original teeth. Ceramic veneers were applied to the front teeth and partial crowns made out of pressable ceramic were used for the side teeth. This has resulted in a highly attractive and long-lasting solution. Different preparation forms were used, as represented in the pictures

A non-metallic full ceramic bridge made out of pressable ceramic to replace a missing tooth. The middle tooth will be replaced by a bridge.

A non-metallic full ceramic bridge made out of pressable ceramic to replace a missing tooth. The middle tooth will be replaced by a bridge.

(Picture: K. Reichel)

Prosthetics, Dentures, Restoration

(Full ceramic, Pressable ceramic, Lithium disilicate and Glass ceramics, Zirkonia, Crowns, Bridges)

Crowns, bridges and partial crowns can be made today out of various material. The most commonly used material today is pressable ceramic. Ceramic, unlike material that was often used in the past, contains no metal, and like real teeth is translucent, making it very popular as the restorations look quite natural. Pressable ceramic is available in a large range of colours, which allows exact matching to existing teeth. The term “Full Ceramic” is now taken to mean any non-metallic restoration.

Pressable ceramic can be applied in a number of areas:

- Thin frontal veneers

- Minimal invasive inlays/onlays (1mm)

- Partial crowns and crowns

- Small bridges for front teeth and incisors

- Implants – supra-structures

The material can be worked to very high tolerances, is stable, firm, and looks very good. Crowns can sometimes be coloured subsequently to achieve even better colour matching.

A wax model must first be made that can then be turned into ceramic.

(Picture: D. Schultz)

(Picture: D. Schultz)

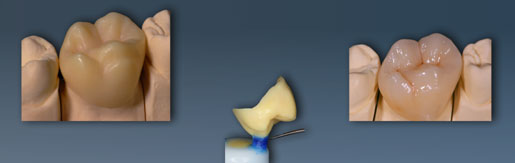

Pressable ceramic incisors. A wax model displaying the morphological bite surfaces (reconstructed using biological criteria) is turned into pressable ceramic using a technique similar to that used in gold casting. This enables food to be chewed most effectively whilst at the same time looking good.

A wax model of a crown sitting on the plaster model (left) prepared for the impression (middle). The coloured pressed crown is shown on the right. (Picture: K. Reichel)

A wax model of a crown sitting on the plaster model (left) prepared for the impression (middle). The coloured pressed crown is shown on the right. (Picture: K. Reichel)

A bridge construction milled from a ceramic block (Picture: K. Reichel)

A bridge construction milled from a ceramic block (Picture: K. Reichel)

Milling/Burring

(Virtual planning, scanning, CAD-CAM, digital data capture)

An additional procedure involves scanning a previous wax model. A scanner gathers data systematically and reliably, which is then used to mill the same shape out of block of ceramic (there are many such kinds of dental ceramic). This process can be used to create single crowns, inlays, partial crowns and bridges.

Copings can also be milled, which are then covered by a ceramic crown or bridge that has been fired in an oven. This layering technique is the same as that normally used with gold fusing.

(Picture: K. Reichel)

(Picture: K. Reichel)

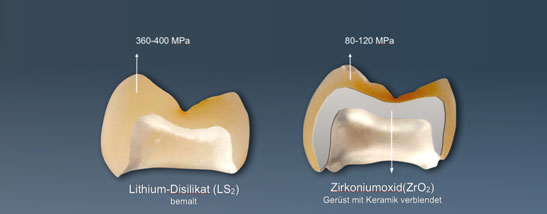

Picture showing two processes of making a crown. On the left a crown has been milled from a block of glass ceramic (lithium disilicate); on the right a coping (shaded grey in the picture) has been milled from a block of zirconium oxide, and then covered with a layered ceramic crown. It is subsequently fired in an oven. The various materials have different degrees of rigidity.

Virtual planning is a software-enabled process that allows a visual representation of the mouth to be created by means of a scan. This is then used to digitally model the tooth replacement which is milled from a ceramic block.

(Darstellungen K. Reichel)

(Darstellungen K. Reichel)

Digital model of a prepared front tooth (left); a milled model taken from the digital scan (middle), and a representation of the complete restoration which has been milled from a single flat ceramic block. (Picture: K. Reichel)

Dental laboratories that use scanners and digitally controlled milling machines are able to create dental items within extraordinary high levels of tolerance and material consistency. This is done by using high density industrially produced ceramic blocks that are extremely stable under all forms of pressure, which is particularly useful if larger connecting elements need to be used – for example between widely spaced teeth.

Prosthetics / Implants

Cone beam computed tomography, panoramic radiography, positioning the implants – Insertion – positioning splint, zircon, abutment, titanium– implant screw, impression coping, implantation process, emergence profile, gingiva formers

It is necessary to take a radiogram before preparing one or more implants to enable the dentist to understand the bone structure into which the implant will be placed. Typically panoramic radiography is used, as well as cone beam computed tomography

Cone beam computed tomography (or CBCT) is a medical imaging technique consisting of X-ray computed tomography that has become increasingly important in treatment planning and diagnosis in implant dentistry. The CBCT scanner rotates around the patient’s head, yielding a volumetric data set. The scanning software collects the data and reconstructs it, producing what dentists call a digital volume. CBCT creates a 3 dimensional picture (a “voxon”, which is a combination of “volume” and “pixel”) of a region in the jaw.

The positioning of the implant is depends on the size, thickness and stability of the bone available, the angle of the implant to the axis of chewing, and the length of the implant. A positioning jig can be created to ensure it inserted exactly correctly.

After a healing period, the implant-healing cap is exposed surgically, and often in the same session with the dentist, a gingiva (gum)-former is positioned to create the emergence-profile, which will be subsequently used for the positioning of the crown, making it look as if the tooth is growing out of the gum, rather than sitting on it. After about 2 or 3 weeks an impression is made using a template that allows the dental technician to create the crown. The abutment (the part which connects the implant to the crown) will be made in the dental laboratory, which is then attached through the previously prepared gingiva. The crown itself is then attached to the abutment. If all this is done well the tooth will appear to grow naturally out of the gum.